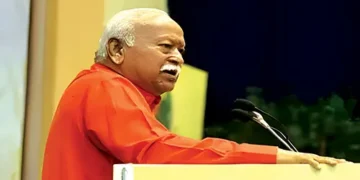

There are voices that wound and voices that heal. Some speak merely to vilify, while others attempt to speak to the soul of a nation. Mohan Bhagwat, the sarsanghchalak of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, belongs to the latter category – an unassuming paterfamilias whose quiet humour and classy candour reflect the organisation’s long-cultivated ethos: restraint, rootedness, and an unbroken belief in Bharat’s historic cultural continuity. His three-day lecture series at the centenary celebrations of the RSS at New Delhi’s Vigyan Bhawan carried a symbolic weight: a reminder that the RSS, founded in 1925 by Keshav Baliram Hedgewar, is not just a social experiment, but a cultural force preparing for its second century.

There are voices that wound and voices that heal. Some speak merely to vilify, while others attempt to speak to the soul of a nation. Mohan Bhagwat, the sarsanghchalak of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, belongs to the latter category – an unassuming paterfamilias whose quiet humour and classy candour reflect the organisation’s long-cultivated ethos: restraint, rootedness, and an unbroken belief in Bharat’s historic cultural continuity. His three-day lecture series at the centenary celebrations of the RSS at New Delhi’s Vigyan Bhawan carried a symbolic weight: a reminder that the RSS, founded in 1925 by Keshav Baliram Hedgewar, is not just a social experiment, but a cultural force preparing for its second century.

For the first time in its history, the RSS chief fielded over 200 audience questions on language, Hinduism, secrecy, population, technology, and caste reservations— that he supports reservations until communities themselves feel otherwise, and that ‘Hindu’ is someone who identifies as Bharatiya and is rooted in Indian culture. One point is not negotiable: infiltrators must be deported. All regional languages, he said, are national languages, while imposing a foreign one is unacceptable.

He threw open RSS offices and shakhas to critics, urging them to see firsthand, instead of clinging to prejudice. In a pointed move against what he called a leftist-driven anti-RSS ecosystem, Bhagwat even suggested “Hum do, hamare teen”—not “do”—as a liberal, but culturally conscious approach to population policy.

The message was blunt: the Sangh is not an enigma. Step inside and see it for yourself – or abandon the manufactured narrative.

The timing of this outreach is critical, as it coincides with a sustained political assault led by Rahul Gandhi, whose critiques have intensified since 2018.

Gandhi has repeatedly accused the RSS of undermining India’s pluralistic ethos, alleging it seeks to impose a homogenous Hindu identity and exerts undue influence over the BJP. His remarks, including calling the RSS a “threat to India’s secular fabric”, have galvanised Opposition narratives, particularly during election cycles. While earlier criticisms of the RSS by Congress leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi eventually waned, Rahul Gandhi’s persistent tirade has prompted the RSS to adopt a proactive, confrontational approach.

By inviting Opposition leaders and engaging with minority communities, including Muslims, Christians, and Buddhists, the RSS aims to dismantle the perception of exclusivity. The scale and ambition of this flagship event – 100 Years of Sangh Yatra: New Horizons – saw about 2,000 participants including diplomats from over 50 countries such as the US, UK, Germany, Japan, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, whose presence underscores international interest about the RSS’s role in shaping India’s ideological currents as a global power.

Thematic categories

The BJP allies were conspicuously present. So were some Congress leaders, but a no-show by Rahul Gandhi showed an unwillingness to debate than accuse. The exercise covered 17 thematic categories, from youth entrepreneurship to national security and cultural identity, aiming to project the RSS as a broad-based, inclusive force to foster grassroots connections, ensuring that the message of unity permeates rural and urban India alike.

For decades, the RSS remained an inward-looking cadre movement, focused on shakhas and discipline. Now, it presents itself as an interlocutor in the global marketplace of ideas. Bhagwat’s formulation of ‘belongingness’ as the Sangh’s core principle recalls an older Indian philosophical tradition: that the self is not isolated, but always situated within a larger whole. He draws from the Vasudhaiva kutumbakam trope – Hindu thought is not sectarian, but universal. He framed Hinduism as rooted in inclusivity and mutual respect across communities. History shows that institutions evolve under pressure. Just as Ashoka, after Kalinga, redirected imperial power into a moral enterprise, the RSS is recasting itself as a reconciliatory force, not a polarising one.

Panch Parivartan

RSS articulation of Panch Parivartan – social harmony, family enlightenment, environmental awareness, selfhood, and citizen’s duties – resonates with older Indian frameworks of dharma. Unlike Western political categories that separate religion, state, and society, Indian philosophical tradition is the ethical, social, and cosmic as an interwoven entity.

Bhagwat’s emphasis on environmental stewardship reframes climate change not merely as a technocratic challenge, but as a dharmic responsibility in continuity with Vedic injunctions about harmony between Puruṣha (human) and Prakṛiti (nature). Bhagwat’s defence of tariffs as a means of protecting Indian farmers was not couched in policy language, but linked to the principle of swa – the au tonomous refusal to surrender to alien systems of thought or commerce. This nationalist vocabulary situates trade debates in the same lineage as swadeshi, a reminder that economic sovereignty has always been central to Indian nationalism.

Ideological scrutiny

Yet, for all its philosophical appeals, the RSS remains under ideological scrutiny of its ‘woke’ and ‘secular’ foes. Critics, including Rahul Gandhi, have portrayed the RSS as a hardline Hindu nationalist organisation that marginalises minorities and promotes a monolithic cultural agenda.

Bhagwat’s words carry weight not just for the movement, but for India itself. If its first century, the RSS was about consolidation and control; its second may well be about interpretation and dialogue. In a world where civilisational states are reasserting themselves – China with Confucianism, Russia with Orthodoxy, the Islamic world with Pan-umma narratives – the RSS seeks to position Hinduism not as dogma but as a global philosophy of belongingness.

Ultimately, the philosophical question the RSS poses is: can a cultural identity anchor a modern nation-state without erasing its plural voices? History teaches that civilisations endure when they can absorb contradiction, not when they erase it. If the RSS can sustain dialogue with its critics, engage minorities as participants, and solve its own internal fissures of caste and language, it could transform itself into a truly integrative force.

Meditative experiment

In this sense, the centenary campaign is not just an organisational exercise, but a meditative experiment. It asks whether the word ‘Hindu’ – which once meant simply the people of the Indus – can be rearticulated as a universal ethos of kinship in the 21st century. As the RSS moves into its second century, it should sustain its inclusive approach, ensuring minority voices are not just invited but actively heard.

It must address internal issues about caste and regionalism, and foster a truly pan-Indian identity. By leveraging digital platforms, the organisation can amplify its message to younger audiences, countering misinformation while promoting its vision of ‘belongingness’.

Finally, it should engage constructively with critics like Rahul Gandhi, using dialogue to bridge divides rather than entrench them. When Bhagwat threw open RSS offices and shakhas for others to see, the message was about transparency – we are Bharat and have nothing to hide. Step inside and see for yourself, or abandon the manufactured narrative. The true measure of this centenary is whether a villager in Bastar, a student in Aligarh, or a worker in Chennai feels fraternity together. For India, the question endures: can we build unity without erasing difference? The RSS’s response will shape not just its own future, but the destiny of Bharat itself.