Prabhu Chawla

Dwelling endlessly on historical grievance is not a pathway to national renewal. It is, more often, an admission of political insecurity. A leadership that governs by prosecuting the past rather than articulating the future reveals a deeper unease. It unintentionally reflects an inability to generate momentum without resurrecting old antagonisms. History is meant to reflect a narrative, not replace it.

The advice is hardly new. George Santayana famously cautioned that those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it. Yet, Santayana’s insight is routinely misapplied. Remembering history is not the same as weaponising it. Winston Churchill, himself no stranger to historical manipulation, understood this distinction well and warned against allowing bygone conflicts to eclipse contemporary responsibility.

Political thinkers across centuries have reached the same conclusion. Niccolò Machiavelli observed that only weak rulers and the powerful habitually denounce predecessors to conceal their visible infirmities. Franklin D Roosevelt, confronting the Great Depression, rebuilt American confidence through action, not by endlessly indicting Herbert Hoover. Deng Xiaoping engineered China’s economic revival by abandoning ideological score-settling in favour of pragmatic reform.

The axiom holds across cultures and eras. Serious leaders move forward and insecure ones look back.

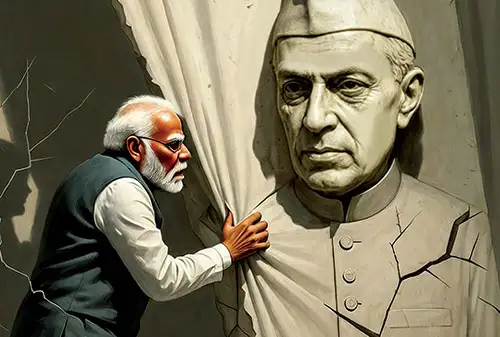

This pattern now defines a conspicuous feature of India’s contemporary political discourse. In the vibrant but fractured arena of modern Indian politics, historical fixation has become not an occasional rhetorical flourish, but a governing method. Nowhere was this more evident than during the winter session of Parliament, where the ruling BJP, under Narendra Modi, repeatedly transformed legislative debate into a prolonged trial of Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi.

Earlier, during the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, these two long-deceased figures were invoked with striking frequency – often more than urgent contemporary issues such as agricultural distress, urban migration, or youth unemployment. The implication was unmistakable: that India’s electoral future hinged less on policy prescriptions than on retrospective moral judgments. This tendency intensified during the winter session, where debates on the 150th anniversary of Vande Mataram and on electoral reforms devolved into extended critiques of Nehru and Gandhi.

In his parliamentary address, Modi accused Nehru of weakening Vande Mataram by limiting its official rendition to the first two stanzas, allegedly under pressure from Mohammed Ali Jinnah and the Muslim League. He framed the decision as an act of appeasement that fractured national unity. The charge that Nehru surrendered cultural pride in 1937 to divisive forces ignited the House, eclipsing the commemorative intent of the debate and reframing a historical compromise as ideological betrayal.

This was not an isolated intervention. Home Minister Amit Shah reinforced the narrative throughout the session, situating Nehru and Gandhi at the centre of discussions ranging from national symbols to electoral integrity. The BJP’s objective appears increasingly explicit: to recast India’s foundational narrative through a nationalist framework, portraying Nehru and Gandhi as architects of appeasement and division rather than nation-builders.

Relentless scrutiny

For over a decade, this scrutiny has been relentless. Nehru’s handling of Kashmir, his commitment to secularism, his foreign policy, even his private correspondence have been repeatedly mined for political ammunition. Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence is selectively referenced or subtly diminished. However, the ideological implications of his assassination are left conspicuously implicit. Institutional memory has been reshaped through renaming exercises: the Nehru Memorial has been rebranded, and locations honouring these figures have been recast.

A particularly symbolic episode occurred on December 15, when Parliament passed the Viksit Bharat Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission Gramin Bill, replacing the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. The Government highlighted substantive changes – raising guaranteed workdays from 100 to 125 and introducing performance-based evaluation. Yet, the removal of Gandhi’s name was widely interpreted as deliberate legacy erasure.

The programme was detached from the moral vision that inspired it, even as its technical features were repackaged as reform. Home Minister Amit Shah recounted Congress-era electoral manoeuvre and catalogued alleged instances of “vote theft” stretching from Nehru to Indira Gandhi. Yet, controversy emerged recently over the “missing” Nehru papers, with the BJP accusing the Congress of misinformation before confirming that the documents had been transferred to Sonia Gandhi in 2008. The episode reinforced a familiar pattern: accusation first, clarification later.

Forceful responses

Responses from the Congress and liberal intellectuals have been equally forceful, though no more productive. Sonia Gandhi condemned what she described as an “orchestrated campaign” to vilify Nehru. Historians such as Irfan Habib emphasised Nehru’s role in laying India’s industrial foundations, while liberals highlighted Gandhi’s global influence on civil rights movements. Priyanka Gandhi Vadra proposed allocating a dedicated parliamentary session to catalogue all grievances against Nehru – so that, as she put it, the chapter could finally be closed.

This cacophony reveals the debate’s fundamental limitation. It generates heat, not governance. It obscures the complexity of India’s founding moment, reducing it to caricature. Nehru’s failures – his romantic idealism toward China, the 1962 debacle, aspects of his minority policy – deserve scrutiny. But so do his achievements: establishment of technical institutes, infrastructure projects like Bhakra Nangal, and a constitutional framework balancing unity and diversity. Gandhi’s non-violent resistance not only secured independence but inspired decolonisation movements worldwide. To minimise them is to amputate India’s own intellectual lineage.

Why, then, this backward gaze? The answer is political convenience and not conviction. The irony is stark. India under Modi has much to showcase. Since 2014, the economy has more than doubled, making India the world’s fourth-largest. Annual growth has remained in the 7-8 per cent range. Foreign direct investment exceeds $80 billion annually; exports have surged towards $800 billion. Poverty has been substantially reduced through targeted welfare. Digital infrastructure has transformed service delivery and created millions of jobs. Infrastructure expansion, renewable energy leadership, defence indigenisation, and diplomatic milestones such as the G20 presidency testify to real progress.

Self-defeating fixation

Against this backdrop, the fixation on Nehru and Gandhi appears not only unnecessary but self-defeating. A confident ruling party should amplify its own lineage. And the BJP has it in abundance like Modi’s governance record, Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s nuclear diplomacy, economic liberalisation, and the Golden Quadrilateral; initiatives like Atmanirbhar Bharat. Instead, mid-level leaders amplify distorted narratives on social media, spreading claims that collapse under scrutiny and inadvertently keep Nehru and Gandhi in public consciousness.

The unintended consequence is revival. A generation distant from independence has now been forced to revisit Nehru’s Discovery of India and Gandhi’s writings, prompted by controversy. Raj Ghat remains a site of reverence, visited annually by Modi himself and foreign leaders. Nehru’s internationalism echoes in global diplomacy. What might have receded into textbooks now dominates headlines.

This is the paradox. In attempting to bury Nehru and Gandhi, the BJP has resurrected them. The ghosts refuse to fade because they are constantly summoned. Ultimately, India’s ascent demands synthesis, not erasure – integrating Gandhi’s ethics, Nehru’s institutional vision and Modi’s administrative energy. Nations rise by forging futures, not by endlessly exhuming their past.